by Jim Farrell

© Jim Farrell and The Thunder Bay Historical Museum Society

This work was first published by the Thunder Bay Historical Museum Society

as a catalogue to its exhibit of Robert J. Flaherty’s original photographs, 1973

Its original title was Robert Flaherty in Northwestern Ontario.

Photos accompanying this article are from the collection of the Thunder Bay Museum.

“He is not a motion-picture director by profession, but an engineer and explorer interested in people.” Louis D. Froelick, 1923

“…a half dozen geniuses took a crude mechanical device for reproducing motion and created of it an art, an art with its own laws, techniques and potentialities. Certainly, no one has played a more important role in shaping that art than the late Robert J. Flaherty.” Arthur Knight, 1953

Northwest

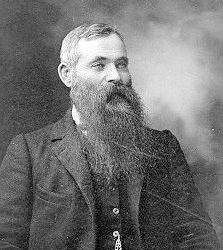

Robert Flaherty came to Canada at the age of 12. He was intelligent but troublesome. His father, just appointed manager of the Golden Star mine near Rainy River, Ontario, was certain that a wholesome life in the out-of-doors would do Robert good. The rest of the Flahertys stayed in Houghton, Michigan. Bob had been born in Iron Mountain and the family fortunes had depended up to that time on mining operations in northern Michigan. But now prospects of iron, silver and gold in the rough bush lands across the border attracted mining men of every variety. Bob and his father were two among many who probed the Precambrian forests to get at their riches.

n a camp-like atmosphere, with fishing, hunting and the friendship of the Ojibway, the boy formed a deeply sympathetic bond with his surroundings. His schooling was a more difficult matter. No one really questioned his natural abilities, but neither could anyone bridle his abundant energy and impish sense of humour.

Upper Canada College, in Toronto, didn’t know what to make of him. Here was a rough and ready lad fresh from the hinterlands who was bilingual (English and, from his mother, German), musically adept, a “natural” geologist and able to mix with students of every social stratum. What finally sent Bob home appears to have been a bowling game played in the dormitory halls. It seems that porcelain water pitchers were used for pins.

Turn-of-the-century Port Arthur (now Thunder Bay), where the family moved, was a better place than Toronto anyway. It was isolated by hundreds of miles of wilderness from the nearest city of note (unless you counted its rival twin, Fort William, which not many Port Arthurites did.) Canada’s Lakehead was a busy harbour with railroads and the remnants of an old fur post (Fort William). Lake Superior was four blocks from Flaherty’s front porch and his new school (Port Arthur High School) just across the street.

Bob’s ability with the violin was a sign of genius, insisted his music professor — if only the boy could discover “discipline”! Despite the criticism, Flaherty applied real enthusiasm to his diverse interests and photography (a new hobby) grew to be a passion. He was determined to make “beautiful pictures” even if it did mean lugging a bulky camera and tripod into homes, soda parlours and classrooms.

But the senior Flaherty seemed intent on legitimizing his son’s talents and enrolled him in the Michigan School of Mines in Houghton. Although the subjects were more to his liking, Bob could endure the rigid routine only seven months. In that time, however, he met the school president’s daughter, Frances Hubbard. She was a beautiful girl who loved music and the forest. There was an understanding that developed between them: they should meet again. The girl’s parents thought both of them much too young for such decisions; but even a careful mother had to admit that the boy created “a presence” in any room and any group.

If Robert Flaherty’s formal education was at an end, he had to fund some means of paying his own way. He worked in a copper mine then tagged along on survey assignments with some of his father’s crews. Before long he had proven he could take on such tasks alone.

Above a paint store on Port Arthur’s Lincoln Street, he installed himself in one-room bachelor quarters. There was a piano (and, of course, his violin), the tools of the map-maker, canoe paddles, tins of tobacco, a tea service, a caricature of Napoleon, and dozens of reproductions of Renaissance art.

His local friends were no less cosmopolitan in their tastes. Captain H.E. Knobel, an experienced adventurer, could list among his active interests: engineering, geology, anthropology, ornithology, Italian Renaissance art, exploration, big game hunting and music. Knobel’s lodge on Loon Lake housed his grand piano, The lawn was terraced with flowers and a winding stream crossed by tiny bridges. When Knobel sat to play Chopin, people boating on the lake stopped to listen.

With good conversation exhausted, Flaherty might have simply admired the Captain’s paddle, into which had been burnt the names of the lakes and rivers he had travelled. Added last were “Hudson Bay” and “James Bay” . . . the lands beyond the watershed that Flaherty knew he must see.

By 1906 he was on the move — but first to the West, making money by surveying and prospecting. Along the way (probably in Winnipeg) he met Ashton Alston, the factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fort Churchill in northern Manitoba. These were still the days when a factor’s arrival and departure were saluted with cannon fire. The post was a combination of industry, tradition and pioneer life. Alston provided Flaherty with another incentive to go north to see it all for himself.

In British Columbia, where his travels eventually took him, Flaherty sought out and discovered marble. However, it was his accomplishments with the violin that made him a frequent guest at Government House in Victoria. About this time Frances reappeared in his life. She had just returned from her musical schooling in Switzerland, and they became engaged. It would be a long engagement — eight years.

Back in Ontario, Flaherty took up prospecting, this time in the region north of Lake Huron. It was his father who offered a suggestion for getting into the Arctic. Sir William Mackenzie was building his Canadian Northern Railway. If there was iron ore as well as furs to be carried out of the Arctic, he might consider extending the line to reach them. At least he could be counted on to support a one-man expedition to find the ore. And Robert Flaherty was the man to do it . . . so Flaherty guaranteed him.

Almost 40 miles west of what is now Timmins, Ontario, Flaherty bid railroad comfort goodbye and stood facing the Groundhog River. With one companion (an Englishman named Crundell) and a 17-foot Chestnut canoe full of supplies, he set out to look at new lands. From the Groundhog into the Tattagami, from the Mattagami into the Moose, it was a fast five days on the swollen rivers that brought him finally to Moose Factory. And beyond Moose Factory was James Bay . . . and the Arctic!

North

Flaherty’s official assignment was to prospect the Nastapoka Islands. In September of 1911, at Charlton Island, where the fur ship from England put in, he first met Inuit. They and the factor explained to him that his travel plans were impossible. It was too late to sail and too early to sledge. The first lesson for man in the Arctic was a hard one: patience is the only weapon against weather.

He did make it to Fort George, a post just below the tree-line. It was the land of the Naskapi Indians who decorated their caps and garments with designs such as Lapplander use.

Flaherty managed still another trip, this time to Great Whale. The stories he was accumulating about a chain of islands known as the Belchers caught his interest. The Inuit claimed they were more than 100 miles long, while Admiralty charts showed them tiny. More interesting still were the descriptions of the terrain. Flaherty developed a theory that the islands might be continuation of the rich Minnesota iron ore bodies. At any rate, he set himself the challenge of “rediscovering” and mapping them.

In the following winter (1912), he was again thwarted. Wide cracks in the ice of the bay made a crossing impossible. Flaherty changed direction, put together a party of teams, guides and hunters and set off across the Ungava Peninsula. He went east to the sea by one route and came west by another, mapping all the way. He was the first white man to do it.

In August of 1913, he stood on the deck of a little ship (his ship), the Laddie, in St. John’s harbour, Newfoundland. He was determined to find the Belchers by water, and to winter there. The harbour disappeared behind him; all around and underneath his feet were the products of his planning and provisioning. The strangest items on the cargo list were a piano, motion-picture camera (Bell & Howell, hand-cranked), and developing and printing equipment.

Up to now he had taken only still photographs. They were records of where he had been and whom he had seen. Most striking of these were his portraits of the people of the North. By a combination of charm and artistry, he captured beauty and heroism and made them seem real. Could the illusion of movement make them still more real?

Weather delayed his rendezvous with the Belchers for one more year. Then he found them the hard way — by running aground. While the Laddie was overhauled at Moose Factory, Flaherty went south to marry Frances in New York City. There was time for a honeymoon, settling down in Toronto and even some editing on his film footage.

By August of 1916, the mapping of the islands was complete and his dreams of rich ore confirmed. It had been a shame to see the Laddie go but in the previous winter she had fed their stoves. When it was time to leave the Belchers, Flaherty divided up his goods amongst his Inuit friends. To Rainbow went his Winchester; to Tookalook, his canoe; and to Wetalltok, his piano.

In spite of his respect for the traditional life of the Inuit, Flaherty could not ignore the changes the white man brought with him, and he must have deeply regretted the effect of his gifts. Wetalltok later decided that “the box with many insides” was worth more to one of the post factors than to him. He hauled it on his sled nearly 300 miles to sell it. Tookalook tried to cross the bay with the canoe strapped to his kayak. Wind capsized the rig, and Tookalook was never found. Rainbow, crazed with the starvation of a bad season, terrorized his village with the Winchester. He had to be shot in self-defence.

Back in Toronto, Flaherty sat down to edit 70,000 feet of exposed film. He completed the task, but a cigarette dropping onto the nitrate film stock destroyed his work in a flash. Articles on the Ungava Crossing and Belcher Island adventures were published in the Geographical Review in 1918, but, after the loss of his film, they weren’t much comfort.

Flaherty was more determined than ever to have his film of the Inuit’s story. Another expedition was funded. The money now came from a fur trading company, Revillon Freres, and the sole purpose of the project was a film. Flaherty took two Akeley hand-cranked cameras, a tripod with a newly-developed gyro head, as well as developing, printing and projection facilities. Headquartered in Cape Dufferin, he hired a well-known hunter named Nanook (“The Bear”) as the principal character in his film.

Nanook actually became something of an associate producer since he was responsible for transportation, built a cut-away igloo for interior scenes, sheltered the cameras from the cold, and even suggested script ideas.

There were many obstacles to overcome when shooting film in the Arctic. Water required for developing and printing were hauled to the equipment in buckets. Graphite was used as a lubricant for the film cameras since oil would freeze. Film froze too. In -30 temperatures it shattered like glass in the camera gate.

Despite the hardships, Flaherty was gathering together to elements of a good film, one that showed the north’s beauty and cruelty together. It was nothing more and nothing less than the story of Nanook’s life: hunting and travel. The costumes had to be authentic which meant having them made. Westernization had already touched the Inuit, and traditional clothing was rare. Flaherty screened his rushes for Inuit audiences and learned a good deal about movie-making from their reactions.

After just a year, the work was done. Nanook had bigger hunting scenes planned; he couldn’t see why the work should stop. While Flaherty waited for his return ship, Nanook moped about the shore. As many white men as there were pebbles on the beach would see the film, Flaherty explained to him, but Nanook could not understand how such a common thing as his life could interest so many. He followed Flaherty’s ship in his kayak. Then it became no more than a speck. Within a few years, the name and face of Nanook would become synonymous with “Eskimo”. By that time, Nanook would be dead of starvation.

South

This time the editing in Toronto went well. The lessons learned from first mistakes were invaluable, and the added vitality of the hunt sequences was just what was needed to make the film more than a travelogue. A man named Charlie Gelb helped, and Carl Stearns Clancy assisted on the titles.

New York City was the place to sell a film, and Flaherty tackled the job like he would a journey through tough terrain. Commercial motion picture distributors were afraid to risk money on something called Nanook of the North which had no stars, no plot and no sex.

Pathè (a French company like Revillon) was finally persuaded to take it on. Mr. Roxy’s new Capitol Theatre was ideal, but Mr. Roxy was hard to convince. Flaherty, who hadn’t lost a bit of the cleverness of his school days, set about handpicking an audience and coaching them in their reactions. Into this well-laid trap, he put Roxy. Flaherty gambled that he’d trust the reactions of an audience more than his own. He won.

In June of 1922, the film opened at the Capitol. Within weeks the crowds were growing larger and the critics more eloquent in their praise. Suzanne Sexton of The Morning Telegraph called it “one of those unusual features so original in theme and treatment that it makes one wonder why so many directors cling to hackneyed plots and settings.”

Urban American audiences might tend to romanticize over the brave, simple and good-natured Inuit, but none of them seemed to escape untouched by the hidden power of Flaherty’s film. Soon there was talk of Nanook as the sign of a new age in film making, of education and entertainment combined on the screen. Nanook of the North would later be called “the world’s first documentary.”

Flaherty and his close friend, John Grierson (who began Canada’s National Film Board) were to set the standards for a new kind of motion picture. Famous Players (later Paramount) invited Flaherty to make a picture in Samoa. He was given simple instructions: “Bring back another Nanook.” His career as a geologist and explorer was at an end.

In the years to follow, Flaherty would be known for Mona, Man of Aran, Elephant Boy and The Louisiana Story. His travels took him throughout the world but never back to the Arctic.

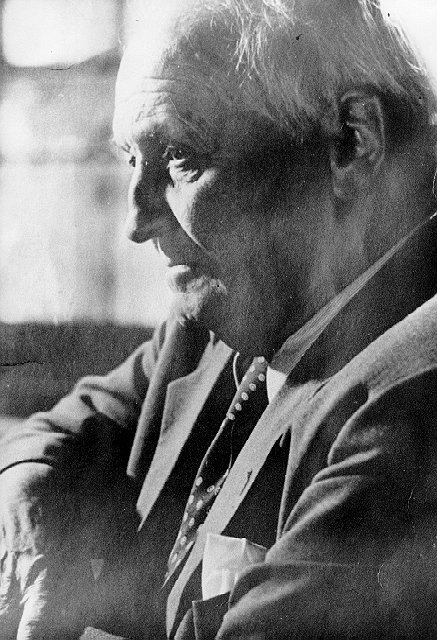

He was a man who worked for the respect he earned in his lifetime; it was not surprising that such a man would get tired. On a last visit to his family, before his death in 1951, Flaherty seemed distracted. Riding along the Superior shore, he gazed out of the car window and into the depths of the bush. Perhaps he was thinking of his early life, of times and people who were now alive only in memories . . . and on film.

Jim Farrell

Thunder Bay, 1973

with research continuity by Rae Katherine Farrell

Sources

Interviews:

- Mrs. H.A. Ruttan

- Mrs. Susan Ross

- Mrs. C.G. Taylor

- Mr. Hugh Cummins

- Mrs. Prue Morton

Research:

- The Thunder Bay Historical Museum Society, Robert Joseph Flaherty Collection

- Arthur Calder-Marshall, The Innocent Eye (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World)

- Richard Griffith, The World of Robert Flaherty (New York: Duell, Sloan & Pearch, 1953)

- Robert J. Flaherty, in collaboration with Frances Hubbard Flaherty, My Eskimo Friends (Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1924)

- Robert J. Flaherty, “How I Filmed Nanook of the North,” World’s Work, vol. 44, Sept. 1922

- Robert J. Flaherty, “Wetalltok’s Islands,” World’s Work, vol. 45, Jan./Feb, 1923

- Robert J. Flaherty, “Winter on Wetalltok’s Islands,” World’s Work, vol. 45, Mar. 1923

- Robert J. Flaherty, “Two Traverses Across Ungava Peninsula, Labrador,” The Geographical Review, vol. 6, Aug. 1918

- Robert J. Flaherty, “Indomitable Children of the North,” (Photographs), Travel, Aug. 1922

- Robert J. Flaherty, “Life Among the Eskimos,” World’s Work, vol. 41, Apr. 1923

- L.D. Froelick, “Flaherty, New Movie Prophet,” Asia, vol. 23, June 1923

- Winifred Holmes, “Ethnography and the Cinema: Robert J. Flaherty’s Valuable Work,” Discovery, vol. 1, Apr. 1938

- H.V. Fondiller, “Bob Flaherty Remembered,” Popular Photography, vol. 66, Mar. 1970

- “Documentary Daddy,” Time, Feb. 3, 1941

- Current Biography, 1949, pg. 199

For more recent information about Flaherty’s still photography see:

Robert J. Christopher, “Through Canada’s Northland: The Arctic Photography of Robert J. Flaherty”, in Imagining the Arctic, edited by J.C.H. King and Henrietta Lidchi (British Museum Press, 1998)