1822-1914 | Artist and Engineer

by Thorold J. Tronrud, Ph.D

William Armstrong first made a name for himself as a civil engineer – as his work on some of Canada’s early railways attests – and as a pioneer in the use of photography for industrial purposes. But is was his art that has given him a place in history.

Armstrong emigrated to Canada from Ireland in 1851 and settled in Toronto where, as partner in the firm of Armstrong, Beere & Hime Civil Engineers, Draughtsmen and Photographers, he put his technical skills to productive use. His early watercolours showing industrial sites, forts and harbour scenes in and around Toronto won him recognition, and even a prize or two, but they alone would not have secured him anything more than a minor footnote in the history of Canadian art. A trip to Lake Superior in about 1859, however, close on the heels of his partner Hime’s exploratory trip as part of Henry Youle Hind’s expedition to explore the areas of the Assiniboine and Saskatchewan rivers a year earlier, changed Armstrong’s life. For here, on the craggy shores of the world’s biggest lake, he found material for a lifetime’s work.

We can only speculate on what motivated Armstrong to paint this remote corner of the country. Like so many others of the Victorian era, he may have succumbed to the lure of adventure and felt a need to show the world what he had discovered – dramatic cliffs, forests and waterfalls, unique people and activities. Perhaps he was swept away by the patriotism and promotional zeal that pervaded Upper Canada in these years, or he may simply have felt a need to document the frontier before it changed beyond recognition, for he seldom romanticized the land he painted.

But Armstrong also had eminently practical reasons for his interest in the region, both as an engineer and as an artist. In a letter dated 7 April 1860, he applied to the Canadian Department of Public Works for a job placing landmarks and buoys to mark the route between Collingwood and Fort William. At least twice more, he sought employment from the same department enclosing testimonials from his former employers in 1863, and offering to make drawings of the northwest route for a Pacific railway in 1871.

Armstrong felt his art as well as his engineering skills could be useful both to the government and to private industry. Thus he offered to sell what he termed his “large collection of original water color drawings of scenery in the mining and agricultural districts around L. Superior” to the Department of Agriculture in 1877 for a promotional display at the Paris Exhibition.

The government, having already turned down his previous offer of works for an exhibition in Philadelphia, replied characteristically, that it had no funds. Some fourteen years earlier Armstrong had unsuccessfully offered his services to Edward W. Watkin of the Atlantic and Pacific Transit and Telegraph Company who was then promoting a cross-continent telegraph link. The proposed line was to go through Northwestern Ontario and across the prairies to the west coast, passing through territory inhabited by remnants of the Sioux (Dakota) nation which had been driven out of the U.S. only a year earlier. “The expense of sending a party across the plains in the present temper of the Sioux,” wrote Armstrong, “would be costly in the extreme and very dangerous.” He offered, instead, to produce “either Crayon or Water Colour drawings” of the terrain from original sketches he had purchased.

A postscript to this letter suggests another reason for Armstrong’s avid interest in the Northwest – the lure of mineral wealth: “A friend of mine,” wrote Armstrong, “a practical miner has just returned from a tour through the mines of Lower Canada, he says the indications and quality of ore at Fort William are far better. If you have any friends who think of taking lands from the Government for sale at Fort William I know all the lots which have copper and lead running through them and will be happy to advise them.” Armstrong himself boasted that he had “120 acres with Copper on the Kaministiquoia R. and F. Wm.” and both of his one-time business partners, H.L. Hime and Daniel Beere, had mining claims in the Thunder Bay District. Armstrong painted mine sites such as “Herrick’s Camp, Amethyst Harbour”, “Shuniah Mine, Port Arthur”, and “Mandelbaum’s Camp”, and admitted that he “went through the exploration lines on purpose to gain knowledge of minerals.” How many of the artist’s illustrations originated in his search for the mother lode?

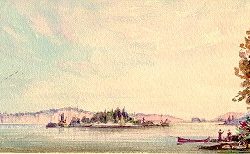

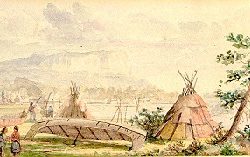

Regardless of Armstrong’s motives, his paintings of Native encampments, dense forest, rocky outcrops, the great inland seas that are the upper Great Lakes, waterfalls, ships and boats, the remnants of the once great fur trade and the mining sites that were, at the time, taking over the region’s economy provide us with the only clear, early images of the region we call Northern Ontario.

The record of Armstrong’s travels are obscure. We know for certain that he travelled to Fort William (now the city of Thunder Bay) and its vicinity, probably for the first time, in 1859 and then completed a series of sketches which were later, as watercolours, presented to the Prince of Wales. (These images still remain in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle). He visited Thunder Bay again, for a short period, in the spring of 1870 probably as one of several artists and interested spectators who accompanied Wolseley’s troops on the first leg of their journey to Red River to put down the first Riel Rebellion. (There is no evidence, as many have claimed, that Armstrong participated directly in this military expedition. Indeed there is strong evidence to show that could not have done so). The sheer abundance of his paintings of Lake Superior, Nipigon and Thunder Bay which are dated 1867 strongly suggests a third visit in or about that year – not an unlikely eventuality given the regularity and relative ease of ship travel on the upper great lakes by that time and Armstrong’s avid interest in mining ventures. There is no evidence to suggest, however, that he ever journeyed farther west than the Lakehead. It is doubtful, as well, that he visited Lake Superior again after the early 1870s for his vision of the region, as depicted in the multiple copies he made and sold of his more successful early works, right up to his death in 1914, remained frozen in time. These later works reflect none of the changes the region underwent in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; he painted no northwestern railways, urban settings or busy harbours. His images capture the essence of Northwestern Ontario as it existed before the dawn of its industrialization and this is, by itself, a major accomplishment.

For further information about Armstrong read: William Armstrong, 1822-1914 by Janet E. Clark, Thorold J. Tronrud and Michael Bell (Thunder Bay: Thunder Bay Art Gallery, 1996)

Armstrong’s paintings appears on the market from time to time and many museums hold examples of his works. The images appearing above and below represent some of the original paintings in the collection of the Thunder Bay Historical Museum Society.